What Knowledge Workers Can Learn From Chefs

On personal workflows in the modern era

It’s 9:00 AM on a Monday.

You have a 10-page report to finish and give to your boss on Tuesday and are eager to do a great job on it. You check your email. 30 unread messages. You start picking them off one-by-one… until you think, “Wait. I need to finish my report.” You open your calendar, hoping to find pockets of free time. “How did my day fill up with so many meetings!?” Your Monday was free of meetings last time you checked so you must have received a ton of meeting invitations Sunday night.

You start figuring out which meetings you can skip but your first one is at 9:30. Your boss wants an update on the report. Great. The last thing you want to do is update your boss on how you aren’t done with the report. You need way more time to actually finish it, but you open it up and try and make at least some progress before your meeting. Until…

“Hey!!! How was your weekend?!”

You tell your colleague it was great (hiding the fact that you spent a lot of Sunday afternoon working on your report because god knows it’s hard to do this in your office…). You want to work on your report but you ask your colleague how their weekend was because you’d feel badly if you didn’t.

“So much fun! I went to the museum on Saturday with my partner, and then we went skiing the next day…”

After chatting with your colleague, you check the time. 9:34. Shit! I’m late for my meeting.

At The Ready, we help organizations change the way they work. We believe organizations must care about their operating system — their underlying principles, beliefs, systems, and practices — to thrive in our volatile, complex, ambiguous, and uncertain world.

Just like an organization, people have underlying behaviors, beliefs, and habits that serve as a system in the way we work. As our world rapidly changes, how people get their work done will become more and more important.

Almost all knowledge work requires personal organization.

Yet most schools don’t teach personal organization and we enter into the chaos of our work lives expected to wing it (or somehow have magically figured it out on our own).

Mise-en-place

In the culinary arts, there’s a French phrase called mise-en-place which means “everything in its place.” In professional kitchens, it refers to the setup required before cooking. Ingredients are prepared and organized so when it comes to the actual cooking, the cook doesn’t have to spend an ounce of willpower thinking about which ingredient is where. Everything is in its place.

The concept of mise-en-place goes beyond how a chef organizes themselves in the kitchen. As my colleague Odaywrote about, mise-en-place is almost a religion of all good chefs. “As a chef, your station and its condition, its state of readiness, is an extension of your nervous system… The universe is in order when your station is set up the way you like it.”

Niki Nakayama, Executive Chef at n/naka.

There’s already tons of disorder and chaos in organizations — why not organize the aspects we have control over in a way that gets us to our state of readiness? Perhaps the mise-en-place of the knowledge worker is organizing one’s computer default settings, configuring email and Slack notifications, keeping a clean office desk, and even tossing out things in your “work bag” that you don’t need. (The universe is totally in order for me when I clean out my bag of unfinished coffee shop stamp cards.)

In Work Clean, mise-en-place for chefs is more than just having ingredients prepped before cooking. It’s a philosophy and system for what chefs believe and do. The author Dan Charnas writes:

“What habits make you successful?”

“How strongly are you willing to hold on to your regimen of good habits in a world that will tempt you to ditch them, often without any immediate consequence?

“How much are you willing to keep your own focus despite the chaos around you?”

This is what it means to have a mise-en-place. It isn’t just about preparedness, minimalism, or order. It’s about having the habits and systems in place that allow you to exercise your values.

The Similarities of Holacracy & GTD

There are plenty of great workflows and strategies about how to work effectively: read Getting Things Done, Deep Work, stuff by James Clear, or zenhabits if you’re looking for more on this.

Instead of dedicating this piece to writing a step-by-step framework, what I do want to emphasize is this: the changing nature of work demands that we should continually assess and refine how we work. If an organizational operating system is the principles, practices, and beliefs that allow the organization to best achieve its purpose, an individual’s operating systemare the habits, behaviors, and beliefs that allow them to best achieve their own purpose.

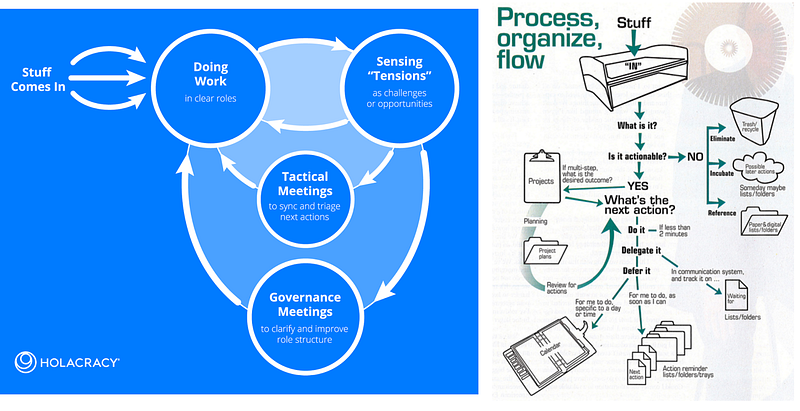

Think about how similar the personal-focused Getting Things Done is with the organizational-focused Holacracy. Holacracy is a complete, packaged operating system organizations can use to better achieve their purpose. Holacracy involves inputting and processing “tensions” and turns these tensions into proposals or next actions.

Left: Holacracy, Right: GTD

Getting Things Done is a complete, packaged personal workflow that people can use to organize the way they work. Gettings Things Done involves inputting and processing “stuff” and turns stuff into next actions. If Holacracy is the most featured and most debated organizational operating system for organizations, GTD is the most featured and most debated “operating system” for individuals. What’s more is the David Allen Company, the company whose name is the founder and actual author of Getting Things Done, operates using Holacracy.

I think what’s more important isn’t so much how effective these two systems are (that’s for another Medium post) but how similar these two systems are. They both involve processing stuff and turning things into next actions and are complete, packaged systems that help a purpose (an organization’s or an individual’s) be better served.

Personal Workflows in an Uncertain World

Uncertainty is here to stay and the value of traditional organizational long-term planning is starting to be questioned. Since all personal workflows involve planning and organizing, could this mean that personal workflows also fall short when uncertainty is high? Maybe not, if we take planning and organizing for what it is: mastering the expected so that we can attentively deal with the unexpected. Personal workflows enable us to plan for what’s certain so that we’ll be ready for what isn’t.

Just as we are seeing a shift in organizations assessing and refining how they work, I hope to see a shift in people assessing and refining how they work. Systems-thinking on a personal level, if you will. People who reflect and work on their systems will not just do what they dream of doing, but will do it in a relaxed, confident manner even as the world around them continues to be uncertain and chaotic.

Like that 10-page report. With mise-en-place, it’s a piece of cake.