Seven lessons I learned from building a self-managed company that changes the way the world works

From one of our Ready Retreats in Essex, MA. Photo by Spencer Pitman.

From one of our Ready Retreats in Essex, MA. Photo by Spencer Pitman.A Retrospective of my time as an Organization Designer at The Ready

On my first day at The Ready, I wasn’t handed a project by a boss.

I remember the day very clearly. I packed my bags and moved to NYC from Irvine, CA four days before. I had been itching to start my first day. I’ve been eager to jumpstart my career in redesigning the way organizations and people work.

The Ready was my dream company: it was a self-managed organization that was focused on being the best in the world at organization design. An organization who’s writing and theory I deeply resonated with. An organization comprised of individuals I would learn a lot from in the next three years.

I asked the company’s founder, Aaron, “Which project should I start obsessing over? What would be best for me to work on?”

He responded saying,

“At The Ready, your job is to figure that out. At The Ready, finding out where you can best contribute is entirely up to you.”

Three years, six client engagements, eight internal strategy retreats, and twenty-five more teammates later, my time at The Ready has come to a close.

To say the least, building a self-managed consultancy that is helping large organizations change the way they work is a unique experience. You are constantly learning your way into three things:

1. What does it mean to build a self-managed consultancy?

2. What does it take to be a positive citizen in a self-managed organization?

3. How might we shape our consulting approach so that our clients are best supported in their journey to transform the way they work?

Each question contains shifts in the way we traditionally think. Building a self-managed consultancy is not like building any other startup. Behaviors that benefit your team and org in a self-managed context are different from behaviors that benefit a more traditional workplace. Helping clients change the way they work demands a different way of consulting from what we’ve seen before.

I’ll use these three questions to frame seven lessons I’ve learned during my time at The Ready. I can easily go on about the lessons I’ve learned, but I wanted to highlight the seven ones that came up for me most throughout my experience. Each lesson could be expanded into blog posts of their own, but for the purposes of keeping this post to just one, we’ll go broad rather than deep.

Let’s dive in.

What does it mean to build a self-managed consultancy?

1) It means being experimental, but being deliberate about it.

In a self-managed organization, everyone has the authority and autonomy to propose an experiment aimed to improve a process, structure, or way of working that hold the organization back from doing its best work. Having the authority to propose changes and learn from them is awesome — we get to design the kind of company we want to work at. But reaping the full benefits of being experimental requires a framework and some thoughtfulness. At times, we could have been more clear about the hypothesis we were trying to validate, established what the guardrails for safety were, and retrospected whether the experiment actually validated or invalidated our hypothesis. The shadow side of being an experimental organization is a system that is overly chaotic, and we definitely learned this lesson ourselves. We’ve learned to take stock on how things are going and recognized the need for us to be deliberate about designing our experiments almost in a way a scientist would: what’s our hypothesis? What’s our experiment design? Who do we hope will benefit? What happens when we fail?

While being experimental takes a willingness to try new things, it also takes careful thought and consideration. Being disciplined about using a framework (before deviating from it) helps with this.

2) It means committing to being mature about power dynamics.

The last client team I was a part of consisted of three members: me, Sharan, and Yehudi. None of us held the title of “project lead.” Instead, throughout our collaboration, we noticed who gravitated toward certain teams at the client and who gravitated toward what kind of work. Yehudi tended to own our work with the senior leadership team, I tended to own our work of building our internal transformation coaches, and Sharan owned our partnership with the customer innovation team. We took those observations and consented to each person having decision rights (technically for each role, but that’s a separate point) such that the role “owning” the work with that team would have final say over decisions regarding our team’s involvement with that team. So Yehudi had final say over any decisions regarding our work with the leadership team, Sharan with the customer innovation team, and me with our transformation coaches.

Our hypothesis was that by making explicit our decision rights, we’d operate more autonomously as a team, ask for permission from each other less, find a healthy balance between collaboration and divide & conquer, and ultimately increase our impact at the client. Obviously, we collaborated, but we didn’t default to collaboration for every single piece of work — we collaborated on problems that were high-stakes and/or highly complex. Each of us still provided input, suggestions, and even open disagreement (lots of it!), but we all acknowledged that the decision right owner had final say.

We weren’t perfectly mature about power dynamics, but we owned it. And our co-created decision rights allowed us to be more autonomous and better support our client.

Sharan and Yehudi rockin’ it.

Sharan and Yehudi rockin’ it.What does it take to be a positive citizen in a self-managed context?

3) It takes reaching out when in doubt.

At The Ready, you don’t have a boss or project manager constantly checking in to make sure you’re doing okay or need help. But this doesn’t mean that self-management is “everyone working their own shit out individually.” It means that the impetus is on you to reach out when you need help.

This was a thing I struggled with and consciously worked on. Whenever I felt stuck on a problem or decision I needed to make, I veered towards working through it on my own. “If I just work harder, I’ll get unstuck” and “If I show my colleagues I can solve this on my own, I’ll be perceived as competent” were the stories I told myself. My colleagues helped me see that this pattern wasn’t serving me, my colleagues, and my organization, so I made a point to default to asking for help when I felt stuck on a problem. And here’s what I realized: asking for help actually leads you to be more trusted by others, not less. Others will notice your humility and the fact that you aren’t afraid to ask for support when you need it.

When in doubt, reach out.

4) It takes doing a few things well, not doing all the things.

As a self-proclaimed achievement-oriented person, I find ease in having my work cut out for me. I like having a clean, prioritized to-do list so I know exactly how I can contribute and be of most value.

The thing with being an achievement-oriented, “get shit done” type of person in a self-managed company is that it’s so easy to self-generate projects, ideas, and actions for yourself to the point where your the items in your task manager keeps growing and growing. This is why I had to be even more critical about what work deserved my full attention and what work didn’t, frankly. I had to be good at personal prioritization — knowing when to focus on the one to two things that will yield the most value, and knowing when to switch off my “work mode” so that I can spend time with loved ones, do things I enjoy, and come to my next workday energized, refreshed, and focused. As Jason Fried puts it, do the enough thing—don’t do everything.

Knowing this, I knew I needed to have enabling constraints. I carried the habits I’ve created in my undergrad of doing a Weekly Review, not working past dinnertime, getting eight hours of sleep every night, and exercising into my job at The Ready. I wasn’t perfect at it, but I’m glad I set these as standards to strive towards.

Building Nirvana with VSECU's former Transformation Core Team. Photo by Will Watson.

Building Nirvana with VSECU's former Transformation Core Team. Photo by Will Watson.How might we shape our consulting approach so that our clients are best supported in their journey to transform the way they work?

5) Ruthlessly understand their organization’s context.

Dave Snowden made a great point on how leaders can create change in a complex system:

“To change a system, don’t push it towards predetermined outcomes. First, deeply understand its context. Then nudge it in a better direction.”

Organizations are complex systems (as opposed to complicated systems), and in complex systems, you cannot predict what actions will lead to what outcomes. You cannot take a practice that applied elsewhere, replicate it in a complex system, and expect it to work. You can understand the context and nudge it towards a direction that serves everyone.

It’s funny, in most of my previous engagements, the client wants to immediately start with you recommending a best practice for them. “Just tell us what we should do.” People are very used to taking what’s working elsewhere and applying it in their context as most people’s mental models of an organization trend towards it being a complicated system rather than a complex one. In these moments, it’s tempting to offer a recommendation and give them what they want, but doing this ultimately won’t serve them. Instead, my former teammates and I used these moments as opportunities to educate our client on how starting with implementing a practice without any understanding of their context wouldn’t benefit their organization’s effort to transform. We found ourselves saying “We’ll get there, and we have plenty of tools and frameworks, but let’s first gain a crystal clear understanding of where the obstacles and opportunities.”

6) Lead with principles, not practices.

Practices are a means, not an end. Introducing new practices are a means to help clients shift their way of working towards principles that symbolize their ideal way of working.

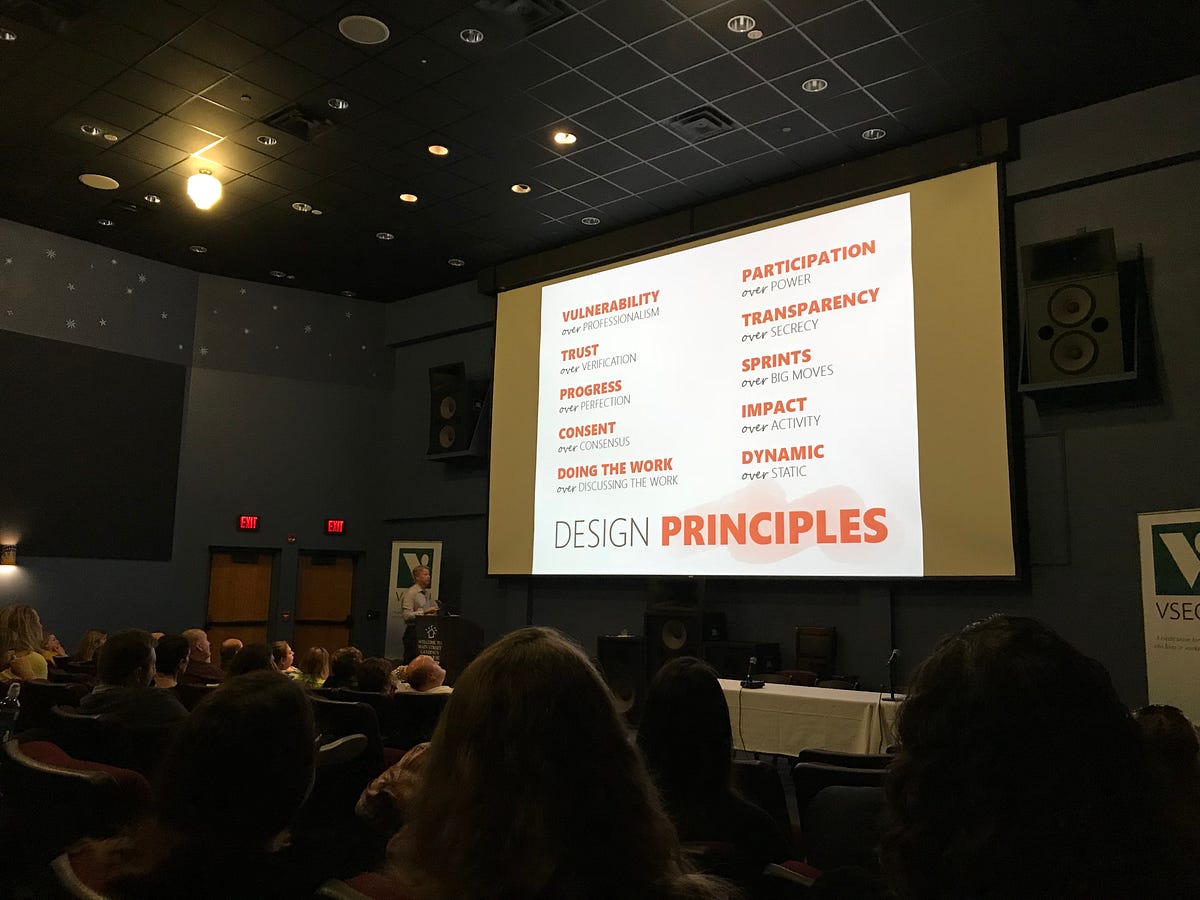

It’s important to ground your transformation engagement in principles and making the connection between how the practices you introduce get them towards those principles. At VSECU, we introduced nine key principles at the beginning of our engagement. VSECU took this list as inspiration and revised the list, adding their own flavor to it and applying it to their context. Their set of principles ended up being the north star of their transformation. Their principles informed decisions they made and experiments they tried as they were evolving their organization’s way of working.

VSECU's CEO Rob Miller sharing org design principles at an all-hands.

VSECU's CEO Rob Miller sharing org design principles at an all-hands.7) In everything you do, build their capacity.

Ever hear of the saying, “Great consultants work themselves out of the job?”

When a client has developed the skills and capabilities to solve problems and continuously improve on their own, you know you’ve done your job as a consultant. In every workshop we were facilitating, artifact we were creating, and leader we were having 1:1 conversation with, my teammates and I made sure to design our experience so that there’s some aspect of it that is improving our client’s capacity. One example of this is how my teammates and I built Transformation Core Teams in some of our client organizations. The Transformation Core Team was comprised of individuals fired up to drive change in their organization, who committed to learning org design theory and how to facilitate, coach, and agitate change with our support.

Seeing a client who’s built their capacity reminds me of why I do what I do. Nothing beat the rewarding feeling from seeing a client facilitate a workshop, coach a team, teach a colleague a new tool/process, and cause a positive ruckus in their organization.

Changing the way organizations work is a privilege

My former colleague Kathryn Maloney once shared that “the work of helping organizations transform is a privilege.” These words could not sum this piece up any better.

It was such an honor to work with the organizations I’ve had the fortune to support. I’m thankful to have helped build a company that is literally changing the way the world works. And I’m most grateful for the curious, focused, and brave individuals I’ve had a chance to work with.

To quote Frederick Buechner, I’m excited to find my next opportunity where my deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.

Here’s to what’s next.